(#344: 5 April 1987, 5

weeks)

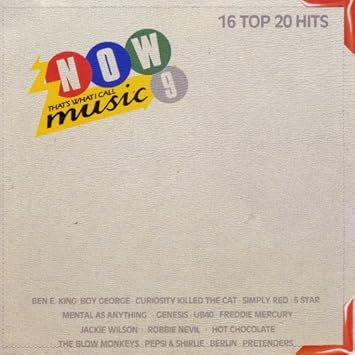

Track listing: Reet

Petite (Jackie Wilson)/Live It Up (Mental As Anything)/The Right Thing (Simply

Red)/Sometimes (Erasure)/C’est La Vie (Robbie Nevil)/You Sexy Thing (Ben

Liebrand Remix) (Hot Chocolate)/It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way (The Blow

Monkeys)/Caravan Of Love (The Housemartins)/Everything I Own (Boy George)/Rat

In Mi Kitchen (UB40)/Big Fun (The Gap Band)/Stay Out Of My Life (Five

Star)/Heartache (Pepsi & Shirlie)/Trick Of The Night (Bananarama)/Take My

Breath Away (Berlin)/The Great Pretender (Freddie Mercury)/Stand By Me (Ben E

King)/Down To Earth (Curiosity Killed The Cat)/So Cold The Night

(Communards)/Jack Your Body (Steve “Silk” Hurley)/I Love My Radio (Midnight

Radio) (Taffy)/Loving You Is Sweeter Than Ever (Nick Kamen)/Manhattan Skyline

(a-Ha)/Sonic Boom Boy (Westworld)/Livin’ On A Prayer (Bon Jovi)/Land Of

Confusion (Genesis)/The Final Countdown (Europe)/Over The Hills And Far Away

(Gary Moore)/Cross That Bridge (The Ward Brothers)/Hymn To Her (Pretenders)

I wondered about that cover for a while. It looked a bit

empty, somewhat frayed, compared with the usual relative sophistication of Now covers. What did those red edges

mean – a menu? An old diary? Then I looked up the TV ad – with Kid Jensen’s

excitable promise of “your own personal hits file” – and realised that it was

supposed to represent that most 1987 of shining artefacts, the Filofax. Oh, the

instant nostalgia! Up there with triple-decker sandwich-sized mobile ‘phones,

that was. You can probably still get them out of Smythson’s – a steal at only

£900 (per page).

Anyway, to the double album itself, which I note boasts only

“30 TOP CHART HITS,” down from the thirty-two offered on the previous two

volumes. I’m not sure why this was – did Now

9 come out too early, only three months after its predecessor? Or, given

the considerable input of WEA and CBS into what went on it, perhaps it was the

problem of having to piggyback a Hits 5½

mini-compilation. Or maybe it had something to do with sound reproduction issues.

Whatever the reason, we are now firmly into 1987 – or

possibly not so firmly, since a good proportion of these thirty songs were

actually hits towards the end of 1986, and indeed some stretch much further

back than that, whether reissues or cover versions. So Now 9 does not put me in mind of the rapidly-changing and always

exciting 1987 that I remember experiencing, but rather puts me in mind of

corporate or industry anxiety. I had hoped that the pained struggle between old

and new would have resolved by this point, but in fact this seems to have been

a trademark of the Now series; ever

more desperate attempts to cling to the past, to tried and tested ways of doing

things and tried and tested people to do them. Despite a track listing which

spans some three decades – from “Reet Petite” to “Jack Your Body” – the

overriding feeling is one of doubt, and perhaps also some fear; several of the

songs refer, directly or indirectly, to the gathering, dark cloud that in

retrospect would come to dominate the time; the same one to which Leonard

Cohen, eighteen months later, would remark that “a naked man and woman are now

a shining artefact of the past.”

Still, it does include a remarkable total of seven number

ones.

Jackie Wilson

Demolishing "Space Oddity"'s six-year record,

Jackie Wilson's "Reet Petite" unexpectedly became the Christmas

number one single of 1986, over twenty-nine years after it had originally made

the top ten. In the interim it had drifted out of circulation, become something

of a prized soulboy rarity. A bootleg 45 reissue was even given the NME's Single Of The Week award in late 1982 by the egregious Gavin

Martin, who swiftly used the opportunity to decry plastic, passionless cocktail

New Pop in favour of Sweat and Soul and Passion. So its surprise late triumph

could be counted a victory for the Real Soul brigade, although the

circumstances of its success could likewise be considered a defeat.

"Reet Petite," Wilson’s first solo hit after

leaving the Dominoes, is one of the cornerstone black pop records; the first

successful song written by the young Berry Gordy, it laid the foundations for

Motown and is thus utterly crucial. As a record, too, it pops and squeals with

a force which seems to overcome Dick Jacobs' deliberately old-fashioned big band

arrangement; not only do Wilson's multiple "ooh"s, "ah"s

and "oo-wee"s reach deep into the backwoods of black music history -

recalling the jump bands of the '30s and '40s - but also set out the ground for

both James Brown and Michael Jackson, and maybe even the erasure of

"meaning" which comes about so remarkably in the record which

replaced it at number one, and appears later in this compilation.

While there is a certain degree of relish in the spectacle

of snobbish soulboys having their "secret" blown wide open, the story

behind "Reet Petite"'s renewed success is depressing. By 1986 Wilson

had been two years gone, following nine years in a coma occasioned by a heart

attack, onstage as part of a Dick Clark oldies revue, in which he injured his

head so severely while falling that he also sustained near-irretrievable brain

damage. There were unworthy tussles over wills and bills; indeed Wilson's

medical bills were eventually met and paid for by Michael Jackson, a frequent

visitor to his bedside. Able to communicate only by infinitesimal movements of

his eyelids, Wilson's last years were wretched, and his passing perhaps a

merciful release.

The record’s renewed, posthumous popularity came about as a

result of a (by 1986 standards) hi-tech video made - irony of ironies - by the

same team responsible for the video to "Happy Hour" by the

Housemartins. It was aired regularly on children's television and became a cult

favourite. But the video itself - featuring stop-motion plasticine puppets of

Wilson and others - was reasonably criticised for tastelessness and even

necrophilia (there are shots where Wilson's head rolls off his neck and along

his arms). Not that this worried the kids who were taken by what they assumed

to be a wacky children's novelty song; the record was duly reissued and became

that season's big seller. And while it did perform the necessary function of

introducing Wilson's music to a new audience who might otherwise never have

heard of it, the video still leaves a rather nasty taste in the spectator’s

mouth. Yes, "Reet Petite" deserved to be a number one – but, to echo

a forthcoming question, did it have to be this

way?

Mental As Anything

Even TOTP – in the

12 March episode sampled at length on the Justified Ancients of Mu Mu’s

aptly-titled album 1987 – What The Fuck’s

Going On? – railed (albeit politely) against the overwhelming presence of

“old songs” in the Top 40. But even the “new” songs weren’t that new; “Live It

Up” had been around since 1985 and only made the top three on account of its

inclusion in Paul Hogan’s first Crocodile

Dundee movie. They were a Sydney bar band and the song depicts a rather

creepy guy attempting to cheer/chat up someone in a “pickup joint.” The

arrangement and delivery suggested that for some people 1969 would always be

the year of Vanity Fare and Joe Dolan. As for the group’s name, as the late

John Peel remarked more than once: “Anyone who tells you they’re mad, isn’t.”

Simply Red, Hot

Chocolate and Sex

Having become quite famous by 1987, Mick Hucknall evidently

decided: enough of the restraint, I’m a ladies’ man and I’m going to prove it.

It is interesting how Simply Red started having hits around the time Hot

Chocolate stopped having them, since they address similar issues in very

different ways. No Errol-style desperate beating around the bush for Mick,

though; “The Right Thing” is an attempt at sex with a conscience, and for all

the indirect debt it owes to Tim Buckley’s “Get On Top,” and despite Hucknall’s

occasional stuffed shirtness (“I told you to stop, ‘You're sleeping out a

lot’/You told me get lost, where's your understanding?”), he just wants to do

the right thing, which in 1987 meant the safe

thing. There was this gathering, dark cloud at the time.

Erasure

Marking, I believe, the first appearance by anything on the

Mute label on a Now compilation –

Depeche Mode held out until Now 17

(“Enjoy The Silence”) – and indeed the first appearance of a duo who will soon

become Then Play Long regulars,

“Sometimes” was introduced on TOTP

with words that were something like the following: “You know what’s been

happening with Alison Moyet since Yazoo split, but you might be wondering what

Vince Clarke’s been up to. Well, here he is…” Three-year continuity of memory!

You wouldn’t get that now (cue baffled pop fans with goldfish-level memories

struggling to remember anybody who had a hit in 2011 who isn’t in TMZ

regularly).

Actually, everybody was glad to see Vince – and Andy Bell –

back on the scene and high in the charts (“Sometimes” peaked at number two,

Mute’s biggest hit since “Only You” four-and-a-half years earlier) and

“Sometimes” is musically a terrific and seemingly effortless pop record; shards

of inevitable melody glide, at times over an unexpectedly chunky guitar riff

with shades of “Everything’s Gone Green,” with more than a hint of melancholy

at its centre, a feeling heightened by Guy Barker’s trumpet solo (Barker was

clearly the go-to musician for melancholy and/or telling trumpet solos in

mid-eighties Britpop).

This is borne out by the song’s lyrics, which initially seem

quite joyful with their talk of falls in ecstasy, and warming each other in the

night. But this scenario is not as idyllic as it might seem: “Ooh, sometimes,

the pain is harder than the truth inside” goes the chorus, followed by “It’s the

broken heart that decides.” Like the amplified return of “You Sexy Thing,” you

get the feeling that this underlines the end of an era, that nothing is going

to be the same after this, that everybody is going to have to be careful and

cautious. And that there will be much hatred and prejudice to be borne until

people grow up.

Robbie Nevil

“C’est La Vie” too is a cover version – the original appears

on gospel singer Beau Williams’ 1985 album Bodacious!

– and the overall impression with Nevil’s version is Junior Giscombe getting

down with a robot Silver Convention (“THAT’S LIFE!” shouts the chorus, rather

than the “THAT’S RIGHT!” of “Get Up And Boogie”). Other than that this might as

well be updated electro Bob Seger; the singer has a dead-end job, can’t get no

satisfaction and wonders what’s the bloody point of it all, only to realise

that that’s just the fucking way it is. It is nowhere near enough, of course,

but Nevil, and his strangely harmonically fugitive keyboard lines, convinced

enough early 1987 floating voters to make it a top three hit here (in the

States, it was what some call a “Terrific Two”).

The Blow Monkeys

I’ve already mentioned soulcialism once, and it was all over

the place in 1987 (as were, ahem, “sonic theft merchants,” but more about the

latter later). A descendent of New Pop, the purpose was to imbue pop-soul music

with left-wing political lyrics, and some did it better than others, notably

its Scottish practitioners – although Dr Robert grew up in Australia, he

actually comes from Haddington, about twenty miles east of Edinburgh.

“It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way” was the group’s biggest

hit, from the excellent album She Was

Only A Grocer’s Daughter which probably would have done much better than it

did – it peaked at #20 – had state radio of the period not been so scared away

by it. But there was no resisting one of the most elegant uses of the Go-Go

rhythm in pop, nor Dr Robert’s Bolan-lives! croon in which he metaphorically

discusses the state of the nation and tries to reassure the song’s subject that

what “we”’ve got just isn’t good enough, and that she (or he?) needs to “ask

for more.” His “Well, I’ve just about had enough of the sunshine, HEY!” is one

of the most heartfelt rejections of Thatcherism in eighties pop, knowing as it

does what too much “sunshine” can do. Great little nod to Elvis at the end of the song, too.

The Housemartins

The original version of "Caravan Of Love" was

released in 1985; written and performed by Isley, Jasper, Isley - effectively

the next generation of Isley Brothers - it is an affecting update on the "People

Get Ready" template; a call to unite which could easily double as a call

to arms ("It's time to stand up and fight"). Although it doesn't

surpass the exacting standards set by the Impressions song (and doesn't

"People Get Ready" bear the sweetest smile of any loaded gun in pop?

Even Lennon had to bow down before Mayfield's genius - the Christmas carol

glockenspiel, the ethereal, benign harmonies all concealing instructions for

uprising and revolution), "Caravan Of Love" again spoke for the

dispossessed of the Thatcher/Reagan era, those who either wouldn't join in or

had been deliberately left out of the party.

In a Britain which, in late 1986, was as divided and

defeated as ever following the aftermath of the miners' and steelworkers'

routs, where the nation's family silver was routinely being auctioned off to

the highest bidder (that winter's "tell Sid" British Gas

privatisation campaign was a particularly loathsome example of free market

brutalism masquerading as comfy homeliness), it is likewise easy to understand

what a song like "Caravan Of Love," with its entreaties to protect

and rebuild "The place in which we were born/So neglected and torn

apart," would mean to whatever was left of the community. In Britain, the

hit version - and the first true acappella

number one - came from the Housemartins, the nearest thing 1986 had to a

people's band; though essentially indie, they weren't quite pop, not exactly

soul and nowhere near folk.

As with Larkin, they were content to remain in Hull, handily

just out of reach of the metropolis, the kind of corner into which all true

poets must crawl sooner or later - the title of their debut album, London 0 Hull 4, was a deliberate act of

protectionism and pride, and for the 1987 Brit awards they deliberately stayed

in Hull to accept their award by video rather than venture down to the capital,

an act which caused much malice on the part of Radio 1 controllers (every DJ,

as I recall, was compelled to read out the same statement about what a disgrace

it was that the Housemartins didn’t attend the Brits when PAUL SIMON HIMSELF

had attended in person. No, eighties Radio 1, you were the disgrace, as we now know).

"Caravan Of Love" was their "winter

warmer" of a Christmas offering; though the harmonies are necessarily simplified

from the original, it is finely sung, and Paul Heaton's cracked lead vocal -

part pleading, part threatening - is an ideal conduit for the message being

delivered. It was their most popular single, and the only mutterings of

discontent came from the music press, who accused UK radio of inherent racism

for playing the Housemartins cover but not the Isley, Jasper, Isley original

(and they may have had a point). By the most bemusing of ironies, its intended

status as 1986's Christmas number one was to be denied by a rearguard action

from that precise direction, resulting in one of the most bizarre and

problematic of all Christmas number ones. That particular story has already

been discussed above.

Boy George

Halfway through side two of the abovementioned 1987 - What The Fuck's Going On?, in

between "The Queen And I" and "All You Need Is Love," is a

lengthy sequence featuring "highlights" from one evening's edition of

Top Of The Pops (Thursday 12 March to

be precise), cut up as impatience allowed, with occasional channel-switching

segments from Channel 4 News, the

golf on BBC2 and adverts on ITV ("More of this could mean less of THIS!"). Hosted by Steve Wright and

the late Mike "Snowy Smithy" Smith - the latter the cousin of the NME's Gavin "Half An Hour Of Aretha

Every Morning To Teach Yourself Dignity" Martin - it demonstrates just how

lamentable the Top 40 of the period looked, and also the degree of seriousness

with which artists treated TOTP at

the time insofar as nearly every featured record is on video.

"Nearly 25% of the chart is comprised of old songs for

the first time ever," muses Snowy Smithy mournfully, as he runs through,

among other sub-delights, Nick Kamen murdering "Loving You Is Sweeter Than

Ever" (see below), "the very subtle Freddie Mercury" having a go

at "The Great Pretender" (ditto) and the life-extinguishing pettiness

of the phraseology employed throughout - "Look! A new song! "Don't

Need A Gun" by Billy Idol is a chart entry at 38!" (no sentient human

being has ever used the term “chart entry.” Nobody has ever released a

compilation entitled Greatest Chart

Entries), "Let's have some Top 40 Breakers (i.e. snatches of videos

they don't have time to play in full)!" The only vague sign of life is

"Fight For Your Right To Party," the video for which is prefaced by

such side-splitting remarks as "This is not a BBC Board of Governors

Meeting...Nor is it one of Peter Powell's better-known gigs."

As the top ten is counted down, Smith announces "Here

come the old songs" (bypassing Mental As Anything's two-year-old

Australian hit "Live It Up" at number five). There's Freddie and his

Platters platter at number four, Jackie Wilson's "I Get The Sweetest

Feeling" at three, "Stand By Me" (see below) down to number

two...

"...and at number one, back on Top Of The Pops for the first time since 1985 (cue huge cheers from

the studio audience, presumably relieved that one of the artists has actually

turned up to perform their hit, despite the fact that the last time this artist

appeared in the TOTP studio had been

in 1984), it's BOY GEORGE!" Cue a quick cut to Bill Drummond roaring

"Fuck that! Let's have the JAMMs!"

The sequence's deliberate blankness speaks for itself; this

represented everything Drummond and Cauty were (up) against, and just over a year

later the JAMMs would indeed be top of the pops with their carefully crafted

and cunning plan. Possibly it's not fair on poor, benighted Boy George, for his

glossy Xerox of Ken Boothe's 1974 chart-topper clearly reached number one on

the public sympathy vote. Following the relative failure of the last Culture

Club album, 1986's From Luxury To

Heartache, George had deteriorated badly, nearly losing his life to heroin,

shrunken to a virtual skeleton, at one stage reportedly given a fortnight to

live. In addition, keyboardist Michael Rudetski, who played on that album as

well as several other dance hits of the period - including "Male

Stripper" by Man II Man and Man Parrish, number nine in the chart the week

"Everything I Own" went to the top - was found dead of a heroin

overdose in George's house.

So the meaning behind his interpreting "Everything I

Own" - "I would give everything I own/Just to have you back

again" - was transparent. The record is otherwise utterly unremarkable

apart from the fact that George's voice sounds shot to pieces; hoarse, slightly

desperate. The public were willing to forgive and embrace him again, at least

temporarily; the Sold album followed

later that year, a scabrous, bitchy and frequently very funny record, and its

title track, released as a single, remains underrated, but neither did much

more than scrape the Top 30. But George has survived, as a highly-respected DJ,

with the occasional film theme or Culture Club reunion or bizarre out-there pop

nugget ("Generations Of Love," "Everything Starts With An

E," the latter put together with fellow DJ and one-time Haysi Fantayzee

rival Jeremy Healy) or spell of community cleansing; at the moment it will be

interesting to see whether he does end up becoming pop's Quentin Crisp.

UB40

Well, you can believe

that this song – one of the few UB40 hits to be sung by Astro rather than Ali

Campbell – was actually inspired by Ali moving into a new house only to find

rats running around it. But these lyrics – “When you open your mouth, you don’t

talk, you shout,” “When you out on the street you practise lies and deceit,”

and, most starkly, “If I had my way, if I had my say/I’d like to see you hang”

– really do leave no doubt who the “rat” really is. A year before the last song

on Viva Hate, too. It doesn’t get

played much, or at all, on oldies radio.

The Gap Band

Don’t think we’ve come across Tulsa’s finest funk band on TPL before but “Big Fun” was their

biggest and last (non-reissued/remixed) UK hit single. There’s not much to it

beyond Charlie Wilson’s tremendous, ecstatic vocal performance – take me to

church indeed – Go-Go timbales and a killer synth bassline which reminds me of

the Human League, but there doesn’t need

to be. This record’s least complicated and most entertaining tune.

Five Star, Curiosity

Killed The Cat and Genesis

Pepsi & Shirlie

A small reminder that once Wham! were considered as a

quartet rather than a duo – so, what happened to the other two? They were

briefly resurgent in 1987, and “Heartache” – which, irony of ironies, was kept

off number one only by “I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me)” – is far bolder a

production (the record was co-produced by Phil Fearon) and far brighter (and

darker) a performance than the likes of Five Star were able to achieve. You can

even hear George ah-ah-ahh’ing in the background of the choruses. Shirlie is

now married to Martin Kemp, and George still comes round to their place for

Christmas dinner. That’s really sweet!

Bananarama

Not their biggest hit, and entirely unplayed on oldies

radio, but it stems from the same well of darkness as “Cheers Then” and “Rough

Justice.” Effectively the trio’s last record with the Swain and Jolley team,

“Trick Of The Night” is the old story of running off to the big city only to end

up as a rentboy, and, though written by Swain and Jolley, may have been based

on someone the group knew in real life. The chorus has harmonies reminiscent of

Microdisney, the vocal layering is one of the most complex outside peak period

Beach Boys, and this is a Bananarama record which deserves re-evaluation.

Berlin

With Top Gun,

American cinema finally located its equivalent to Leni Riefenstahl. There is

such finely-angled, cold beauty to the monoliths of technology which are the

film's real stars that it's scarcely surprising that director Tony Scott didn't

find much use for its human components. Even at a human - or more precisely, an

ahuman - level the film is not much more than a homoerotic paean to machines

and the power and destruction that they can wield. What use has Top Gun for its women? Did Kelly

McGillis' career ever really recover from playing fourth fiddle to Tom Cruise,

his rookie buddy and several dozen magnetically exploding rods of harsh metal?

As a film it is a foolish, smug, alienating endeavour so

utterly in love with the cold rationalism of technology in and of itself that

it imagines "beauty" is enough. It is directed by the kind of mindset

which locates beauty in the bodies purposely falling to their deaths from the

Twin Towers, preferring to be broken in death than incinerated - and in the

malabsorbed wargames which lead to such disasters in the first place.

And yet its "love theme" is one of the great

number ones, with a futurism which could properly define awe. It is hardly surprising

that one of the people behind "Take My Breath Away" was Giorgio

Moroder, the electronic musician who above all others understands not to

discard the human heart at the machine's centre, and so there is a very natural

grace about the huge, rising bass line which emerges like the gleaming corner

of the apex of the newly-built Canary Wharf into the unwary lower right eye of

the helicopter passenger. It stuns but does not flatten. The musical model is

the OMD of "Stanlow" and "Sealand," odes to semi-abandoned

mountain ranges of technology marooned somewhere in a vanishing sea, as though

a torch had newly been shone upon its remoter corners, with perhaps a nod to H20's

1983 Top 20 hit "I Dream To Sleep."

Its power, however, is centred in the extraordinary vocal

performance of Terri Nunn, who negotiates Tom Whitlock's rather arcane lyric

("Watching every motion/In my foolish lover's game/On this endless

ocean") as though it's the most important message on Earth, with the tonal

purity of Olivia Newton-John ("If only for today, I am unafraid") and

also a desperate urgency when required ("When the mirror crashed, I called

you!"), finally dovetailing into her own harmony as the song moves up a

key for the final verse, where happy closure is attained; there is blissful

wonder in Nunn's last "Watching in slow motion/As you turn my way and

say" before sighing "Take my breath away, my love" into herself,

in that it is a request rather than an observation; her voice climbs higher to

little death heaven as the song disappears into the blue vapour. It is a shame

that Nunn's voice has not been put to the extensive use it deserves - her

equally extraordinary contribution to the Sisters of Mercy 1993 hit "Under

The Gun" is the only other example which immediately springs to mind - but

at least Moroder knew how to find the humanity which Top Gun, as a film, seemed to find something of an inconvenience.

Freddie Mercury

Now, if you look at the track listing for the second of

these records, which begins with this, and if you know your pop history, you’ll

see the cunning little conceptual trick or circle that Ashley Abram managed to

complete.

More of that later, but for now, here is extravagant,

outrageous, over the top Freddie Mercury finding solace in a song that was a

hit in his fifties childhood. This doesn’t get played much these days either,

and perhaps there are reasons for that, not the least that it is an

uncomfortable listen. Mercury’s version is not as funny as Stan Freberg’s, nor

as penetrating of the song’s fibres as Lester Bowie’s, but is maybe the most

poignant reading. “Laughing and gay like a clown,” he sings with a straight

face, confessing that there are things about him that you don’t – yet – know.

It is estimated that he knew for certain that he was unwell

around Easter of 1987 – i.e. after “The Great Pretender” had been a hit. But in

his delivery there is some awareness that he knows that there may not be that

much time left, and so the long instrumental coda, reminiscent in some ways of

the “Peg Of My Heart” theme to The

Singing Detective, is heartbreaking, like he had already left the building.

Ben E King

"Stand By Me" was a sprinter compared with

"Reet Petite," taking just under twenty-six years from its initial

chart appearance to reach number one. Its revival was not occasioned by the Rob

Reiner film, which wasn't released in Britain until the summer of 1987, but by

the Levi's 501 TV ad campaign which commercially was one of the most successful

ever. Beginning in late 1985 with an "authentic"-looking series of

'50s/pre-Beatles '60s scenarios of vintage Americana (mostly filmed in

Borehamwood), the soundtrack to Nick Kamen removing his clothing in the steamy

launderette, or immersing his shrink-to-fit jeans in the bath, was similarly

unimpeachable Authentic Soul Classics. The effects were immediate; in 1986

"I Heard It Through The Grapevine" returned to the top ten, swiftly

followed by "Wonderful World," a bigger British hit than Sam Cooke

ever achieved in his lifetime.

The next brace of commercials were launched in early 1987;

for "Stand By Me" there was a queue for a club, admission gained only

by the Authentic red tag on the protagonist's 501s, while for Percy Sledge's

"When A Man Loves A Woman" we had a "poignant" portrait of

a departing GI and his lover at the bus terminal. The going-away present? Why,

a pair of 501s.

This all tied in with the still ridiculous residue of the

1982 Hard Times/ripped jeans non-craze, with Robert Elms on The Tube cheerfully deriding

"Northern scum" (forgetting that the programme was being recorded in

Newcastle; he required a police escort to get back to the airport) for not

wearing limited edition super-expensive 501s with original red stitches. Once

again, everything had to be Real and Gritty. But the campaign worked better

than ever before; a month after the adverts premiered on British TV,

"Stand By Me" and "When A Man Loves A Woman" occupied the

top two slots in the singles chart, the latter thereby doubling its original

1966 performance.

In view of the legion of cover versions and reissues

prevalent in the lists of the time, it can hardly be viewed as a healthy

situation where the two most popular records come from the previous generation,

and there was a kneejerk anti-futurism at work here crying out for someone to

come and blow it apart.

None of this, of course, is the fault of Ben E King nor of

Leiber and Stoller, who (with some help from Carole King and the singer

himself) wrote "Stand By Me." It is indisputably one of the great pop

singles, and there may have been an anxiety to right wrongs, since in 1961 it

only peaked at #27 in Britain, and in the interim had become better known in

the form of Lennon's Spector-produced 1975 cover. As a record it is practically

bipolar in nature, for despite the hopeful sunrise strings and backing vocals,

which appear over the tenements like a welcome dash of early morning spring,

the song appears to be about imminent apocalypse with its imagery of "the

land is dark/And the moon is the only light we'll see" and its dread-laden

visions of the sky tumbling and falling and the mountains crumbling into the

sea. This is a gesture of indivisible faith - maybe not that far away from the

fear-filled bunker of Neon Bible, of which latter more later this week in the

other place - a shield against lament and fear in a world which is swiftly

turning into blood. U2 caught something of that feeling when they cited the

song in "The Unforgettable Fire" - also the closest they ever got to

an Associates tribute - and thus the original sits uneasily as a signifier of

reproduction antique America in another land, increasingly unhappy with itself.

Communards

This was an unnerving number eight hit for a chilly and

uninviting winter. Somerville is in his flat, and he regularly watches the guy

in the flat across the way from him undress. He is hopelessly in love with him.

The music is Wilson, Keppel and Betty lite with a Roy Castle-ish tap-dancing

interlude. His falsetto burns like a laser of forgotten cigarette ash. It still

scares the shit out of me.

JACK YOUR BODY

I had a really bad bout of the ‘flu in January 1987. That

was a month of intense winter cold and deep drifts of snow, some of which I

unwisely attempted to shovel away from our driveway one afternoon. Combined

with an equally inadvisable dietary intake, I plunged into ten days of

debilitating fever and inertia, and as the winter refused to let up my weight

plunged to beneath the nine stone mark (halycon days, perhaps, from that

perspective alone). To cheer myself up I played some of the hardest, most

brutalist music I could find on my shelves - the Beastie Boys' then

hot-off-the-presses Licensed To Ill,

Sly's There's A Riot Goin' On,

Ayler's Village Concerts, PiL's Metal Box (in the original 12"

canister, to make extracting and playing the records even more difficult)...and

Volume One of the compilation series The

House Sound Of Chicago.

That latter might not fit with the rest of the unforgiving

fare, but it did provide a crucial balancing lightness. Its lead track - side

one, track one - was the original, deliciously minimalist 12" mix of

"Jack Your Body," and there is a pungent symmetry about its

succeeding "Reet Petite" to become 1987's first number one single;

the two records placed side-to-side could usefully bookend an entire history of

post-war black pop.

There is no doubt that "Jack Your Body," the first

House number one, is a landmark single which forms a crucial bend in the pop

river. It is now over six years since I began this exercise, and time-wise we

are now about halfway through the story as it stands so far - although with the

increased rapid turnover of number ones in later years, the second half may

take somewhat longer to relate than the first - as far away from "Release

Me" as from "Put Your Hands Up For Detroit," but can we imagine

any of the latter-day dance smashes happening without the example of "Jack

Your Body" to open the floodgates? This represented the exact point where

many people decided to get off the bus; Radio 1's Peter Powell, for example,

remarked with specific relation to "Jack Your Body" that he could no

longer understand modern pop music, and eventually (in September 1988) retired

from being a DJ - if only others had been honest enough to follow his example!

But "Jack Your Body" also stands for the logical

cumulation of several coalescing trends in dance music which had been apparent

for some years. Deriving its name from the Warehouse club in Chicago, House

music began its inexorable rise out of its immediate locality throughout 1984

and 1985. Inspired in equal parts by the deconstructing tendencies of

pioneering hip hop DJs like Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash (though instead of

"scratching" in samples from other records, elements would be

digitally sculpted into the House DJ mix), tendencies in electronic music from

Munich and Sheffield alike (though the surprising New Pop influences would

initially be more apparent in the parallel Detroit Techno movement quietly

brewing at the same time, with Juan Atkins, Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson and

others) and electrofunk itself, taking as its starting point the crucial likes

of D-Train, Sharon Redd and Shannon, House focused in more and more narrowly on

the beats themselves, the feeling and mood supersediing notions of

"song" in importance. The silences between beats became as important

as the beats themselves, but there was still room for considerable fluidity and

flexibility - it was still a broad church which could encompass the stark

minimalism of Phuture's 14-minute-long "Acid Trax," the lush

soulfulness of JM Silk's "Music Is The Key," the unworldly lushness

of Mr Fingers' "Can You Feel It."

Starting in the clubs of Scotland and the North of England

(particularly Fire Island in Edinburgh) and slowly spreading down South (for

the soft Southerners were slow to catch on, besotted as they were by the Guts

and Realism of Rare Groove) - it helped that most dancers saw it as a natural

extension of Hi-NRG - House began to catch on in Britain; shops like 23rd

Precinct in Glasgow were the initial stopping point for those extraordinary,

mysterious, anonymous 12-inch imports like Strafe's "Set It Off" (a

transitional eruption from Brooklyn) and Farley "Jackmaster" Funk's

minimalist Isaac Hayes reshaping, "Love Can't Turn Around" which

latter, nearly a year after its initial appearance in the import racks, crossed

over to the national top ten.

Again, "Love Can't Turn Around" has to be

understood in its ruthlessly functional original mix, but its popularity was in

great part down to the amazing vocal performance of Darryl Pandy - if you can

find the 12" vocal remix (it’s on Now

Dance ’86) you can see House becoming maximalist, with Pandy's great,

swooping arpeggios worthy of Buckley on Starsailor

- a characteristic which slightly nullified the notion of House as faceless,

functional dance music! There were other pointers to what was going to happen

in the charts of the period - think of Colonel Abrams' "Trapped" or

even "Axel F" by Moroder protege Harold Faltermeyer, which latter the

pop mix of "Jack Your Body" most closely resembles.

"Jack Your Body" itself is as minimalist as pop

had dared to become this side of Joe Meek and Lee Perry; a flat but springy

beat, keyboard strokes and basslines out of Kraftwerk, and the total absence of

a centre in its determinedly Baudrillardian environment - everything is

suggested, must be absorbed in the act of dancing (and coincidental or

otherwise ingestion of appropriate chemicals). The voice, as such, repeats the

title over and over, lapping in on itself, mechanically generated, a simulacrum

of a human being - and that is essentially all that there is to the record. Its

influence on the subsequent generation of dance-dominant charts is incalculable

and its effect was immediate; soon House music, in both its original form, its

typically British Acieed mutation and the inevitable (if good) pop cash-ins,

would become an indispensable part of the pop landscape. It was not the entire

landscape in itself - as we are already seeing, 1987 was something of a

stylistic grab-bag where literally anything went (and quite often did). But

"Jack Your Body" - especially in its 33-minute multi-mix 12",

which nearly provoked Gallup to list the record in the album chart on account

of its length - is the beginning of a new time, and much of what is to follow

has to be viewed in its immense and far-reaching light. On the other hand, its

structure takes us back to the fifties and what, in both rhythm and words, what

rock ‘n’ roll was always supposed to be about in the first place.

Taffy

Taffy was actually New Yorker Katherine Quaye, but her

Eurohits were all conceived and recorded in Italy. “I Love My Radio,” one of

the last gasps of Italodisco before mutating into Italohouse, took its time to

cross over, having been released in 1985 (as was, originally, “Jack Your Body”)

and filled dancefloors in Scotland and the North of England. Much played, for

the same reasons that DJs and programme controllers will jump on any record

that mentions “radio,” Quaye performs with a soupçon of regret (“Your voice

reminds me/Across my mind a thousand times/In my mind, confusion”) and an

unquenchable joie de vivre slightly

reminiscent of the Belle Stars.

Nick Kamen

Levi Stubbs would have been in tears of laughter if he’d

heard what Kamen had done to his song, i.e. watered it down to anaemic

nothingness. As a singer, Kamen was a very successful model. But his woeful “darlin’

darlin’”s remind us that for some consumers, looks were all that mattered. In

that respect, he is the unwitting harbinger of the Cowell inferno to come.

Meanwhile, Sean Penn wonders whether this was all such a

good idea.

a-Ha

They are at the airport, saying goodbye, and he can’t stand

it (“How can you say that I didn’t try?”). So winsome acoustic waltz battles

with screaming hard rock in the “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” vein – it was the

old Abbey Road/”Question” trick of marrying

two separate but incomplete songs. But as Morten Harket’s outward ice fights

with his inner fire, you could interpret “Manhattan Skyline” as signifying the

split between old and new; the new must come through, but the old is fighting

tooth and nail to cling on.

Westworld

Briefly hailed as the next Sigue Sigue Sputnik – the group

was put together by former Generation X guitarist Bob “Derwood” Andrews – “Sonic

Boom Boy” was their only real moment. Straightforward electro-punk pop which

came, left its mark and disappeared again. I still like its daft, if doomed,

optimism, and American singer Elizabeth Westwood’s so-WHAT delivery; although

she is not herself a blonde, the song did suggest that what would become known

as “The New Blonde” was on its imminent way.

Bon Jovi

Had you been standing on Exhibition Road, London SW7, on a balmy

Saturday midsummer evening about eleven years ago – to be exact, it was 28 June

2003 – you would have seen an unusual sight. Up the road are walking several

music writers and/or bloggers of high distinction. A few hundred yards away, in

Hyde Park, Bon Jovi are on stage, and they are playing their best-known song.

The music writers in question involuntarily begin to sing along with the

chorus, extremely loudly.

There may be a lesson here about the magic of pop music –

and yes, I was one of these music writers strolling up the gentle inclines of

South Kensington – in that Bon Jovi have rarely, if ever, been “hip” or “cool,”

and yet their rock gets to the places that so much other rock doesn’t reach. “Livin’

On A Prayer” – for that is what we were singing along to (I know who the others

were, but won’t divulge their names here) – is a “Don’t Stop Believin’” that

you can believe.

The song is so uncool that it even depends on a riff from

Peter Frampton’s old guitar voicebox. But I’d much rather hear about the daily

struggles of the working class from a New Jersey guy who knows exactly what’s

happening and why. Jon Bon Jovi’s singing is heartfelt but never pompous.

Desmond Child was brought in to make the song more pop – I expect he helped out

with the chorus – but the whole is done with such forceful hope and optimism

that you can believe what they are

singing and playing. Which is why we sang along to them. Anti-union, Jon Bon

Jovi was asked? Not at all, he replied – I am simply observing what

trickle-down economics does to people. You can always rely on blue collar

Democrats.

Europe

No British rock band could have come up with something as

unknowingly unapologetic as "The Final Countdown." Imagine the

Darkness tackling an anthemic song about imminent apocalypse; Hawkins would be

gurning away in his unfunny falsetto, the guitar solo would be suffocated by

the gigantic inverted commas enclosing and enslaving it, the night flight to

Venus would be but a planet-sized eyebrow to ward off the blasted Cool Police.

But Europe were Swedish, and thus had neither guilt nor

guile. Their TOTP performance of

"The Final Countdown" was a masterclass in 1974 Rock School bits of

business, with their frontman Joey Tempest - I ask you, Joey Tempest! - with

his magnificent sub-David Lee Roth mane of perm, dressed head to foot in

leather but with his permed chest proudly on display, going through all the

tricks; using the microphone stand as phallus, agonised hand pointing towards

sky as he considers the end of Earth and the wisdom of rhyming

"Venus" with "seen us," picking up and spinning the

guitarist around mid-solo...meanwhile the defiantly 1974 synth lead melody

(bargain basement Star Trek, but why

not?) affects its would-be poignancy as 1986 drums cascade like the motors of

the rocket ready to convey Earth's few benighted survivors to another and

better land.

Quite admirable in its way, and clearly appealing to those

same neglected pop-metal punters who had bought "Eye Of The Tiger" and

for whom Metallica and Slayer were perhaps a little too

"progressive," "The Final Countdown" did its Continental

business. Whether Europe ever managed to reach Venus, however, is not recorded;

their follow-up, "Rock The Night," however, suggested that earthly

pursuits maintained a greater pull.

Gary Moore

Almost an Irish Big Country, this, complete with proto-Riverdance jig riffs, but really it could be an ancient folk song. The protagonist is arrested for armed robbery and sent down for ten years. He is innocent but cannot protest his innocence as his alibi involves spending the night with his best friend’s wife. Instead, he will hold his tongue, serve out his decade and hope that everything is still under control when he comes out. A double-edged morality tale whose like was already rare, even in 1986.

The Ward Brothers

They were from Barnsley, they were brothers, “Cross That

Bridge” – a record remarkable for its complete unremarkability – made #32, they

never came close again, and I would have put in “Bassline” by Mantronix

instead. I was a huge Mantronix fan in ’86. Their first two albums, The Album and Music Madness, are Cubist genius. The NME’s Gavin Martin roared in his review of the latter that the end

of music was nigh. So that was good news.

Hymn To Her

The first happy ending to a Now compilation since Now 6,

and this is where we take our leave of the Pretenders. The song was actually

written by Meg Keene, who knew Chrissie Hynde back from their days at Firestone

High School in Akron, and is a feminist anthem which quietly but devastatingly

makes its point, sung beautifully by Hynde (albeit with a touch of Stevie Nicks

wistfulness on occasion).

Lena tells me that a biker Chrissie knew in her Akron days

had the habit of playing the same record over and over whenever he got angry or

depressed. That record was “The Great Pretender” – I don’t know which version

he played, but do know that Sam Cooke’s reading inspired the name of Chrissie’s

band. See what Ashley did there?